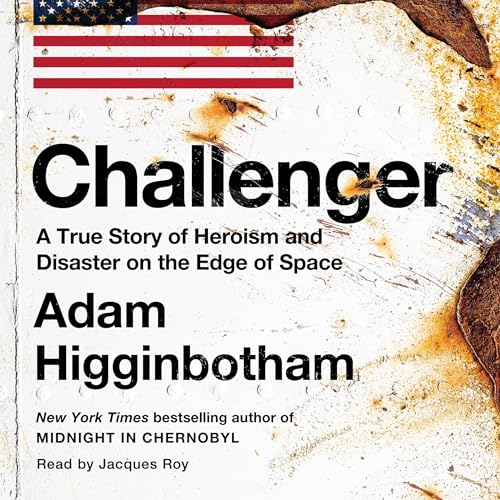

Title: Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space (2024)

Author: Adam Higginbotham

Genre: Nonfiction, Science, History

Publisher: Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster

Pub Date: May, 2024

Format: Audiobook

Reader: Jacques Roy

Steve’s Rating: 5 ⭐ out of 5 ⭐

2024 has offered me quite a reading adventure. To date, I’ve read 90 of my target number of 124 books for the year. About 80 of them have been horror fiction, and the others have been horrific nonfiction. While the former is chock full of books like those I’ve reviewed recently, the latter list includes titles like Watergate: A New History, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980, Fear: Trump in the White House, Homeland: The War on Terror in American Life, Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives… you get the idea.

I get a lot of my book recommendations from The Economist magazine and the NYTimes, and I often scour recent years’ Pulitzer Prize winners in the “general nonfiction” category. I’m rarely led astray with these sources, and if you read like I do, you should check them out. When I saw Adam Higginbotham’s Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of Space winning a metric ton of accolades this year—and I’m fascinated by the shuttle program—I added it to my “must read” stack of downright scary nonfiction books.

For the first nearly 50% of the book, Higginbotham’s inquiry is reminiscent of Tom Wolfe’s early NASA history of the Apollo program, sans Wolfe’s roguish narrative voice, in that Higginbotham details the personal and professional lives of the figures playing key roles in the development of the shuttle program but with a more straightforward historical-journalistic tone than Wolfe’s unique style. (This isn’t a knock on Higginbotham; his approach works well for him, and only Wolfe can be Wolfe.) Then things get extra grim.

Our modern storyteller establishes stakes by walking us through the Apollo 1’s 34-A launchpad fire (27 January, 1967), the key opening sequence we might expect to be book-ended with the Challenger explosion (29 January, 1986). We get the benefit of the author’s excellent archival research in building upon facts and personalities and NASA’s layers of bureaucracy combined with contractors’ perverse incentives to lead us to the undeniable and unchangeable result of negligence and what smacks of downright malfeasance, the solid-rocket-plus-leadership failure that caused the explosion that destroyed the Space Shuttle Challenger, its crew, our faith in NASA (this being a kind of Watergate moment for the agency) and the innocence of every child watching from their classrooms around the country.

I mentioned above that we assume the Challenger explosion will bookend the story opposite the Apollo command capsule fire. That is not the structure of this book, however, as the book’s main argument is better served by instead using Columbia’s February 1, 2003 reentry crackup to close the narrative loop. This choice makes good sense, and it’s why this book stands among the most upsetting I’ve read in years. The emotional charges loaded in acts one and two of this book detonate at the turn to Act 3 when we witness in frighteningly slow motion the events directly leading to Challenger’s explosion. What followed in act three didn’t help me feel any better about NASA and its contractors.

Higginbotham’s argument, put simply, is that NASA did not learn from the Apollo fire that killed its three crew members in 1967. It did not learn from the Challenger explosion, either, which killed seven more astronauts in 1986. And in 2003, seven additional human beings paid for NASA’s biased thinking and broken command system.

Quick sidebar. Cognitive bias often shows up in our inability to measure risks over time and to assess our own past performance. The bias looks like this: we think “It worked that time, so it must be safe” (though not in so many words) or “I didn’t get caught in an avalanche, so I must have made good decisions” where we should be thinking instead, “Wow, I got really lucky there—I should be dead.” This causes us to change how we behave in the present or will act in the future because we confuse survival for success. We tend to overestimate our own expertise in the absence of obvious failures. If NASA had a nickname, it might be “The Hindsight Bias BlunderCorp,” or something cuter or more appropriately terrifying.

“Meet the new boss—same as the old boss” was a line that too pithily expresses what I got from this book. Before listening to it, I’d been under the impression that NASA did all it could to stop these disasters from happening but bad stuff just happens when humans pursue bold and dangerous activities. I’m coming away from it realizing that NASA, in its managers and engineers—along with Thiokol in Utah (where two major separate explosions rocked the solid rocket facility) and its other attendant facilities—saw the train coming and just kind of let it happen because stopping it would have been costly and unpopular. “Oof,” in Gen-X parlance. Major oof. Reading about the train coming, knowing it’s going to destroy everything, learning about the personal lives of its [immediate] victims, and realizing how many kids (including the astronauts’ own kids) watched seven people die on live television… I watched it happen on 9/11/2001, and the feelings of powerlessness it elicits are not dissimilar. What’s that about history not repeating itself but rhyming? Well, NASA is putting that one to the test. It rhymes, and it repeats, as well.

(For those of you listening rather than reading, the audiobook narrator Jacques Roy delivers his prose with compelling felicity; his tone and pacing are a perfect fit for apt expression.)

I recommend this book for all general history, space travel, and political history buffs. In particular, I urge anyone working in a command structure where people’s safety is on the line to take this book’s lessons and incorporate them into your risk management plans. Be better than NASA and Thiokol. You might save lives.

Leave a comment