Notes from the desk of the editor are offered in the interests of personal posterity and transparency for writers and other potential editors who wish to learn from my experience.

the editor

Let’s get nerdy, shall we?

Lately I’ve been reading, like, in order, the Chicago Manual of Style 18th Ed. and an accompanying (let’s call it an appendix of sorts) The Chicago Guide to Copyediting Fiction. The latter is not a style guide, but rather a helpful and well-organized (and much shorter) conversation piece offering advice to us fiction copyeditors. (I’ve also got Chicago’s guide to developmental editing, but that is next in line and will have to wait.)

If you don’t have these books and you’re editing, go pick them up.

So what is a style guide, and why does it matter? And the title said something about a “style sheet”—what’s that?

A style guide is a thorough treatment of all issues one might come across in editing and publishing. Some companies (the NYTimes, for instance) produce in-house style guides, and some go with one produced by another publisher (say, the Chicago Manual of Style / CMOS, or the Modern Language Association’s guide). These are often hefty books (Chicago’s book clocks in at around 1200 pages, small print), and they have exhaustive lists of topics. Check out the CMOS18 table of contents—and its oh-so-sweet index! Let me warn you, super nerds, that this is a rabbit hole you will enjoy. The index, in particular, is what makes the book searchable in its physical form. I adore it.

So why do we use style guides? Well, take the first few pages of any book. They follow a pattern. If the pattern were broken, it might tip you off that the publisher / interior designer who set up those pages wasn’t fully informed about expectations of the industry. And if you’ve got a CMOS, you can just follow the steps!

If you’ve also got Debbie Berne’s The Design of Books (a book I read and love, still), her layout recommendations are much simpler to follow (and are all derived from the CMOS).

Beyond the order of information as it appears in the opening pages, everything from running headers (the text above the body of the text on a page) and differences between recto (right-hand, front-facing pages) and verso (left-hand, back-facing pages), the way most folks set up tables of contents, acknowledgements, and so on. And this is just interior design, which is just to dip a toe into style guides.

Most of a style guide offers guidance on consistency of punctuation (Do I put spaces between the dots in my ellipsis? Yes, I do now), capitalization (Should we capitalize the first letter after a colon? If what follows is an independent clause, then yes, we do), spelling (say, between UK and USA variants), and so on. It handles all the details that come up when one is editing and publishing. Hence the 1200 pages of dense text and a lengthy series of blog posts and Q&As from the editors available on the CMOS website.

The point to following a style guide is to create a consistent novel, story, or collection of stories. The guidance in the CMOS, as with any style guide, is not a set of rules to be followed but rather help for figuring out just when to use italics or quotation marks—in terms of what is recognized as an industry standard.

If you don’t want to stick out like a sore thumb, you need to obtain and use a style guide.

(If you’re working on a shoestring budget, questions like any I’ve asked above may be answered with careful web sleuthing including search terms like “CMOS”—but isn’t it cooler to have the giant book? You can get it on discount if you subscribe to the Chicago Press mailer, which of course I do. I think I got 30% off the CMOS, and you could get 50% off if you catch it at the right time. At seventy-five bucks plus shipping, the cover price ain’t cheap.)

Editing fiction is, of course, different from editing nonfiction. The so-called rules are a bit more fluid and a lot further from rules than might be the case in academic and nonfiction publishing. But inside the covers of a book, there are rules. We (in consultation with our authors, at some times, or the publishing houses we serve, if we’re working on contract) set those rules.

Editing fiction is a bit like running an RPG as a Game Master (a “GM”).

Think D&D. (Try to stay with me, non-nerds, if you’ve made it this far.) In D&D, as with any RPG, the guidance provided in its manuals are not rock-solid rules. They’re suggestions for a system of play. And if the play group (or its GM) determines that something that goes against those guidelines would make their game more fun, they’re explicitly encouraged to disregard the handbook and set their own rules. But the rules at the table need be consistent. Otherwise, we’re playing Calvinball, and everyone will eventually be severely disappointed by the unpredictability of the game.

So, while there are no hard and fast rules incumbent upon every RPG player, there must be rules of consistency inside the fiction co-created by the players at the table.

Editing fiction is like this. We need consistency. If we put some periods inside quotation marks and others outside them (seemingly at random), our audience will rightfully be upset with us for disrupting their fiction-reading flow state. Ditto for other inconsistencies.

The copyeditor’s job, as I understand it, is to act as backstop to prevent our audience realizing they’re reading a piece of text edited by a fallible human being.

We want to make it as possible as can be that they forget they’re reading at all and just drift along in this frigate we’ve provided (per Emily Dickinson).

To help us along, we create a style sheet.

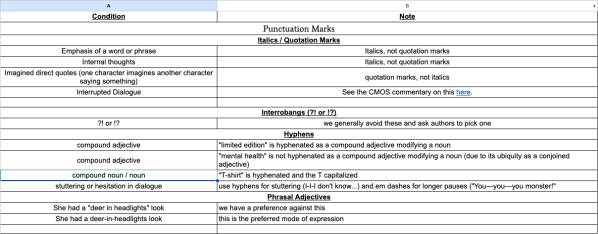

A style sheet is a record of all our decisions about what rules we’re following inside a text (or in a series of texts). To date, I’ve always had this in my brain plus consulted CMOS when I had wonders. I’m realizing I need an honest-to-goodness style sheet. The books I mentioned above will discuss style sheets, but maybe it’s a good idea to offer an example: my own, that is.

You can check out my in-progress style sheet here.

You can copy it, modify it for yourself, add to it in your own variant, etc. (I’m open to suggestions for layout of the sheet!) I’m adding things as they come up in my editing on this second anthology to decrease redundant searches and the likelihood I’ll forget some of the minute decisions I’m making along the journey. It also creates an institutional memory for when I hire other editors (ha!) and is something I can share with authors when I’m offering editorial notes or proofreading the galleys at the end-stage of this project.

This has been my learning process, and I’m hopeful the discussion here is useful to others.

One of the steps I’m taking beyond reading up on editing practices is to join Aces: The Society for Editing and have registered in one of its co-branded courses on editing. I’ll get that going before leaving for France this summer (no editing work will occur while I’m at my residency—I’ll be working on two of my own manuscripts and nothing else, so help me gods).

I do know I’m getting better with editing skills beyond just marking up papers in my teaching role or offering feedback in the sense of a critique group commentary. Contributing authors for WHP have said some nice things about how I work. That all said, I’m at what I consider to be a very early stage in this profession, and know I have a lot to learn.

What has been really helpful for your learning process in terms of editing tools and reference sources? Hit me up in the comments.

Leave a comment