The other night, Sturgill Simpson ran through a truncated “Ripple,” and I was nearly moved, a response music has no trouble getting out of me because it’s a lot of the reason why I’m listening. What stranded me at the edge of emotional release were the suits, ties, and tuxes. I expressed this in that great public forum of my generation’s age in response to someone posting about how moved they were, saying something like, “The music was great; the audience made me squirm.” And it did. It made me uncomfortable. Not the cathartic “Change is coming, and it will make you uncomfortable,” but, well, the kind of discomfort brought about by taking a Wu Tang Clan tape and putting it behind glass.

The response—understandable, I suppose—was that “Music is for everyone.”

Point taken. Music is for everyone. But I don’t think that was the source of my complaint. Right response, wrong premise, in other words. The whole thing didn’t sit right, and it still doesn’t.

I’ll come back to this.

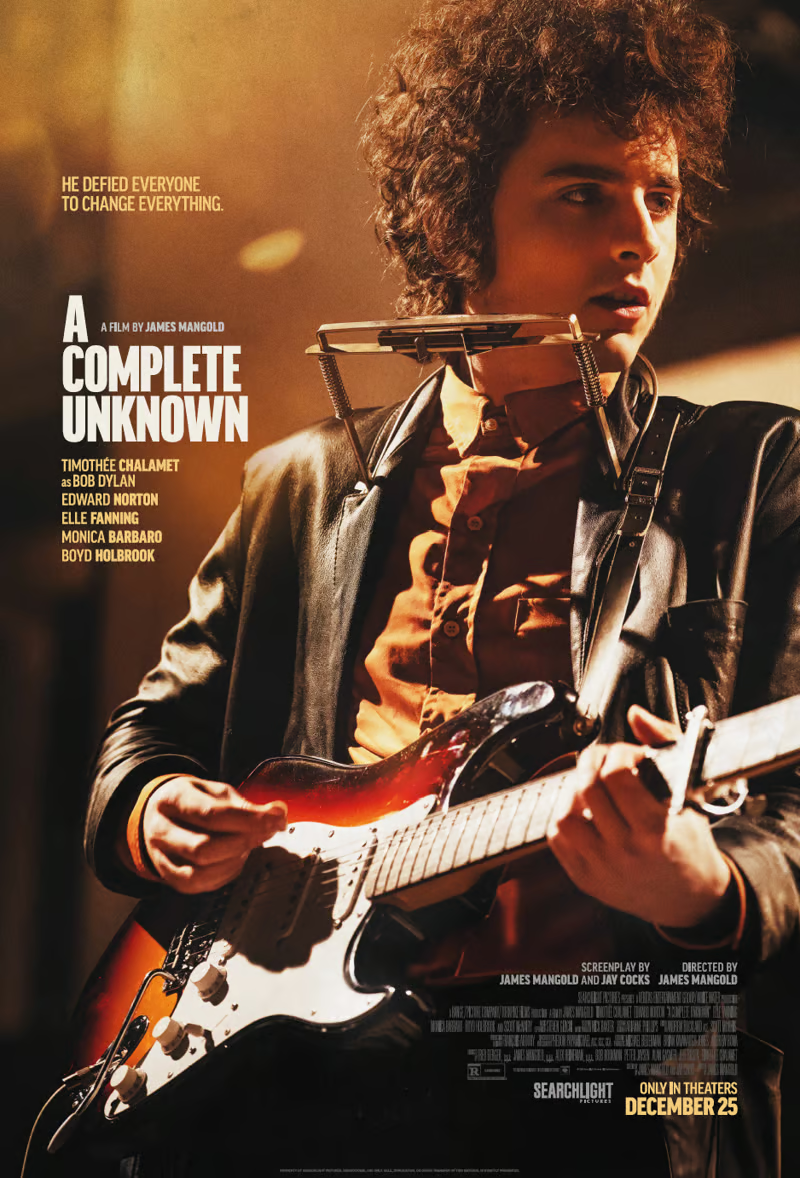

Tonight, December 24th, my wife and I attended the first screening available in our area of A Complete Unknown, a movie on which I’ve been waiting for a few months with cautiously low expectations. Truth be told, I am seeing Nosferatu twice in the next two days and have been much more amped for that… but I underestimated this first film of the odd holiday pairing.

At 2 hours and 21 minutes, I was left wanting more.

Truly, if Mangold and company would have written and shot a version of this film that were six hours long and whose narrative stopped just shy of Dylan’s born-again period—an era of his development I’d like to forget—I’d have been there for it. But I know it would have been too much. The immensity of this thing, emotionally, was perfect.

Just an FYI: This is the spoiler free zone of the review (spoiler warnings will precede musings below).

I had a few thoughts during and after this first viewing, and I’ll share what I think are the main takeaways.

First, Timothy Chalamet plays as good or better a Dylan as Val Kilmer played Morrison. (I also saw some Billy Joel Armstrong in that face throughout the movie, but despite my love for Kerplunk and 1,039/Smoothed Out Slappy Hours, comparing BJA to Dylan is a heresy… then again, the spirit is there…)

Second, the emotional hits came from multiple directions. This film, unlike the previously alluded-to The Doors (1991) and other rock biopics (for real, how do I say that word aloud?), was not a woe-is-me tale of a loner’s descent into addiction and depravity. It was, in my eyes, a story about changin’ times, so to speak. More on this in the “spoiler zone” below.

Third, the layers here were excellently crafted. The core characters all meaningful character arcs, all of whom were humanized and none of whom were usefully demonized. This isn’t a matter of technicality—the fact that all the core characters (and some ancillary ones with key parts) changed meant the whole film had multiple points of emotional connection for the viewer, whether or not those chords were recognized as such.

Fourth: If you’re going in looking for the music merely to accompany the film, you’re in for a treat. The interwovenness (it’s a word, sure) of the lyrics and song choices as relates to the characters’ emotional experiences, often hitting multiple different directions for different characters at the same time, had a profound impact. This set of tunes was not just a soundtrack (think: A Star is Born (2018), a film I loved but which lacked the emotional depth of this film—and I say this only in retrospect and in unfair comparison, as I really appreciated that movie for what it was). These songs meant something, something important, to each character involved in the story at the times they appeared in the film, and those emotions were accessible to us, the viewers—all at the same time, if we stretch ourselves.

To sum up, without spoilers: Go see this movie. It’s superb. It’s tough to overstate how much I believe this movie deserves to be seen. The creators (all of them) deserve recognition for what they’ve accomplished.

Okay. On to the spoiler zone and then to my wrap up about the Grateful Dead’s Kennedy Center honors.

I’ll tell you what hit me pretty damned hard in this film, and maybe this is particular to me: Woodie Guthrie’s slow and mostly-in-the-background death from Huntington’s Disease, a neurodegenerative disorder. It reminded me distinctly of visiting my grandfather before he died. I felt it.

If you’re reading this far, I’m assuming you’ve seen this, but as a writer I tend to think of the bookends of a story being the most important to the message emphasized most clearly in a book or film. I thus appreciated the bookend scenes of Dylan visiting Guthrie in the hospital—at first, as a novice supplicant literally at the feet of his idol; and at last, as a returning prodigal son rejecting the traditional roles of apologetic sinner and unhappy heathen; he’s a rebel in the end. We can stack tales upon tales, here: He’s Oedipus, and he’s killed his father (symbolically in the case of Pete Seegar) to wed his mother (at one point, his other idol’s wife is his backer against her own husband (Seegar)). He’s Odysseus but he’s returned not to take his rightful place but to usurp it from his elders (that one’s a bit of a stretch, but really, it fits!). In A Complete Unknown, Dylan enters the Greystone Park Psychiatric Hospital (I don’t know if they label it as a psychiatric hospital in the film, but that’s what it was) the titular nobody, carrying nothing but his guitar; he leaves with nothing but a gift he doesn’t want on the bike on which he roams, dissatisfied.

At one point in the film—when Chalamet’s Dylan returns to Sylvie Russo (Elle Fanning is fantastic in this role)—I was crying. My wife asked me why and if I was okay, and I hate explaining my tears (or anything, really) mid-movie. I couldn’t. She then asked me why Dylan was going back to this old girlfriend whom he clearly wasn’t in love with as she was him. (I swear, we don’t have big conversations in movies, but once in a while there’s a word or two passed between us.) I said, “He has no one to talk to.”

This was the toughest part of the emotional journey for me: that this guy who tries to remain himself must perform for everyone. On some level, we all get it. And I feel it in my core. Every day, I am on stage; by 4:30 or 5:00 PM, I’m ready for bed. I struggle to maintain the performance everyone expects from me. And this is still not a woe-is-me story, for me or for Dylan. We have to find our places in the world. Dylan made his, and dagnabbit, I’ve begun to find mine. (Yes, I understand the irony of not wanting to compare this Dylan to Morrison but having no trouble comparing him to me.) So why did Dylan return to his ex? She accepted him from the start—bullshit and all (unlike Baez, played expertly by Monica Barbaro, who saw through it immediately). For him to connect with other people, he had to be permitted to be who he felt himself (and wished himself) to be. That thing about “She didn’t go to find herself; she wanted to be something else” is something I’ve said to my wife when we meet folks telling us they’re on some kind of journey to find themselves. (We don’t find ourselves, people. We make choices—or what look enough like choices to be called ‘choices’—and we are what we do. We cannot help but to shape who we are by deciding what to do.)

All this is just to say that Dylan’s story as told in A Complete Unknown is the story about a guy who creates himself through his choices, many of which run against the wishes of the people who raised him up out of the gutter (in a way, right?) and put him on his feet.

The film also bookends a scene in which Pete Seegar defends Guthrie’s “This Land is My Land” in a followup to a contempt of congress charge (he really was called before HUAC in 1955 was later convicted, in a three-day trial, of contempt of congress charges for refusing to answer questions during that earlier appearance) with the general response of Seegar and his fellows to Dylan’s electrified performance at the Newport Folk Festival (what would they have made of Killer Mike’s 2024 appearance? or Trey Anastasio’s 2008 or 2019 appearances? I digress…). In this interior bookending, we get a reinforced message—the same as before—that Dylan is rejecting the old ways, that the old folks should stop criticizing what they can’t understand, and so on.

The filmmakers made a point of noting Dylan’s refusal to appear at the Nobel award ceremony when he won the Prize in Literature (that was way back in 2016!).

Which brings me back to the Grateful Dead at the Kennedy Center.

My squeamishness about the Sturgill Simpson performance didn’t stem from the notion that the music of the Grateful Dead—or Dylan, or Green Day, or Killer Mike, or the Doors—isn’t for the folks sitting primly in their starched shirts and tuxedo jackets at the Kennedy Center. It’s not that that music shouldn’t be played in such a stiff place. By all means, we need these people to hear this music—these anthems of the underrepresented and the unrepentant (because fuck apologizing for being who we are, right?), each in their own times. We need these people to hear, appreciate, and understand this music.

But I maintain: To truly appreciate it, they need to lose the ties and tuxes. They need to stand up and dance.

Dylan didn’t attend the Nobel Prize ceremony, and it gets at what made me so squeamish about full-on emotional release at such a beautiful rendition of one of my favorite Dead tunes. What got me down was the repentant and apologetic supplication these old rockers are bringing to the table by attending at all. This is the thing all rock and roll has stood against since its inception, and it makes me uncomfortable to see our music (punk rock, or rock `n roll, in one guise or another) under appreciated and misunderstood. In short: If you can’t lose the tie, man, you’re missing the point.

Does all this add up for you? Did you see the film? Let me know what you think in the comments below.

Leave a reply to Movie Review: Nosferatu (2024) – Whisper House Press Cancel reply