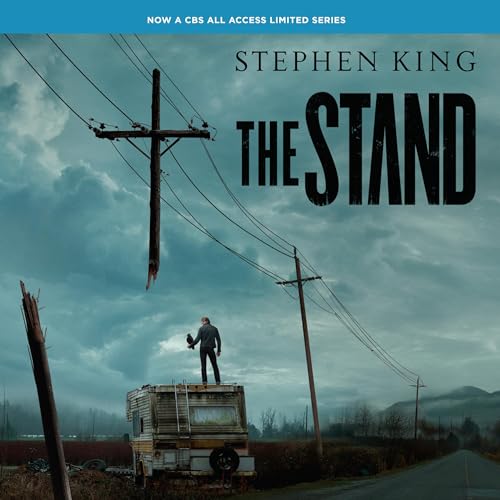

Title: The Stand (“complete and uncut”)

Author Stephen King

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ of 5⭐s

Publisher: Doubleday

Pub Date: 1990 (originally, 1978)

Narrator / Voice Actor: Grover Gardner

When the television miniseries The Stand aired in 1994, I was (almost) eleven years old. I probably saw it on rented videotape a year or so later, and I still remember it. The dark eyes in the cornfield. The corpses in the Lincoln Tunnel. “My life for you!” from Trashcan Man. All of this is vivid some thirty years later.

It was plenty vivid then, too, which is probably why—despite being a King fan from a young age—I refrained from reading this one. As I got older and a tad less frightened, I suspect the sheer girth of this opus kept me away. Between It in the seventh grade, Desperation the summer after eighth grade, and The Dark Tower series in the early 2010s, the only Stepen King works I read were his short stories. Then came The Outsider HBO/Max miniseries and the pandemic in 2020. I started revisiting my childhood favorite author, and in the last few years, I’ve read some ten or twelve of his novels—some for the second time, but mostly with completely fresh eyes.

This year, I’ve gone through some classics: The Dark Half (and then finally watched the film version, which was really good!), Needful Things (yes), Rose Madder (not my favorite)…and the newer Holly (following Holly Gibney on another supernatural noir adventure) and then I came to The Stand, narrated by the now-familiar Grover Gardner. At 48 hours, it would be the longest of the year for me (outpacing Reaganland by three listening hours). I dove in at Christmas and finished on New Year’s Day.

Here are three things that I noticed about The Stand after thirty-five years of general consciousness of Stephen King’s work and a year of diving more deeply (and now with an author’s and editor’s eye) into older and newer novels alike.

I often think of King as descended from H.P. Lovecraft—a very bad man with very good literary instincts and a bizarre take on the world (and the Beyond). Of all of his work, The Stand feels to me the most cosmic in its horror sensibilities. Said Lovecraft in his essay, “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” humans are merely incidental to the workings of beings and phenomena beyond human understanding. That’s what he wrote about, according to the writer himself. And King, in The Stand, is telling a story with not only cosmic implications, but a cosmic focus. It’s bigger than the humans who are involved. Key characters can die—not just because the author is trying to stretch the story and create a bloodline that you’ll want to follow ::ahem:: epic fantasy ::ahem::, but because the cosmic narrative demands their sacrifice. When I think back to The Dark Tower, I think of the cosmic veil being lifted, concretely, and the world on the other side explained and shown to us. (Lovecraft would hate this, I suspect, but it’s the logical conclusion of the shared-universe fictional world he built around the elder gods.)

As much as The Stand is Lovecraftian, it also isn’t. It’s extremely Christian. I knew from the miniseries that there was some religious stuff going on here, but I didn’t remember (more likely: I was not able to see the cultural forest in which I wandered from tree to tree) the heavy-handedness of the conversion story this book communicates. If there’s one key character here for whom this is most true, of course, we’re talking about Larry Underwood, who is “not a nice man” (echoes of The Dark Half here, and I won’t get started on all the intertwinedness of the King universes that resound throughout this epic novel) but turns a corner about as hard as one can (no spoilers, even thirty-five years late). The novel might be read not just as Christian fiction, but as a kind of modern take on what the contemporary Christian is supposed to be like, from a reasonable, swear-friendly point of view. I won’t delve deeper here, but this seems obvious to me at this point. One of the elements of King’s stories that annoys me more or less with every novel I read is that there’s always a clear good guy and bad guy—a clear moral distinction we are all supposed to get behind. I prefer more nuance, since the world is full of moral nuance. That tendency is, of course, on display here in The Stand.

If you’ve read On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, you know the author struggled with what to do with his characters after he’d written them into a corner about 70% of the way through this manuscript (he’d written 500 pages and then got totally stuck). I was looking out for that, wondering what about his characters’ circumstances might have seemed likely to get an author totally blocked, and was amazed at the apparent ease and graceful finish King wrote to end the story and close the circle on these characters. From the look of the finished product, one wouldn’t know he was unable to write for months and reports having zero idea what to do for the rest of his book. Having this knowledge made the last quarter to third of the book especially interesting for me.

Those are the three main things that stood out to me as I listened through The Stand in the year 2024 (into 2025).

The novel is a masterpiece. It’s not my favorite novel, mostly for its Christian overtones, undertones, and general coloration (What happens to the non-asshole nonbelievers? Do we all need to convert?), but I can see how it might be someone else’s.

A final note: If you like Wanderers (Wendig) or Swan Song (McCammon), you’ll probably like The Stand, and if you liked The Stand, you’ll probably like those others.

Five stars because of course.

Leave a comment